Turnover

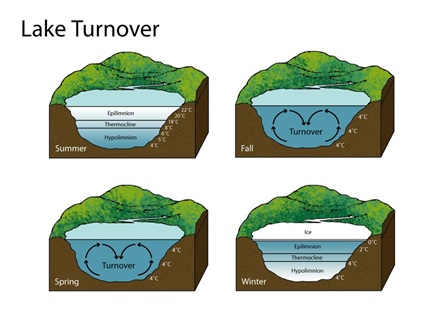

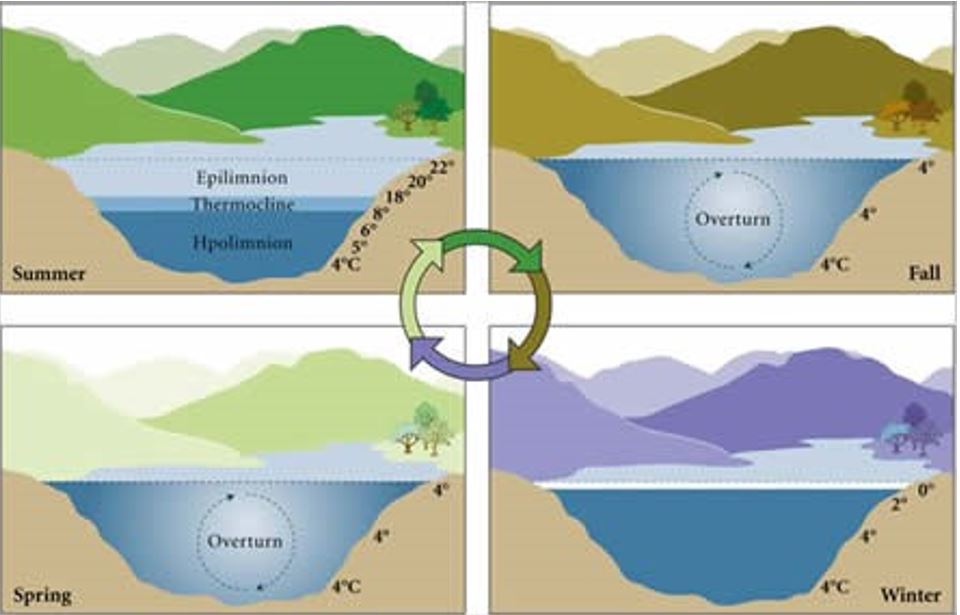

You might know about lake turnover – but just in case, here’s a quick review. Differences in the temperature of lake water keep the water column from mixing for most of the year. In the summer, the warm, oxygenated water floats on top of cold, dense, and anoxic water. The lack of oxygen in the deep water allows nutrients and other compounds to dissolve in that water. At some point in the spring and fall, the temperature will be the same throughout the lake from top to bottom, which allows the lake water to mix, called turnover. Waters carrying oxygen, nutrients, and sediment mingle. This mixing turns the lake water murky, and algae can take advantage of all the nutrients that are carried up into the light.

Our three lakes mix at different times

Rippowam, the smallest and shallowest of our three lakes, mixes first because the small volume of water changes temperature most rapidly. That means in the fall, water temperatures in Rippowam are lower than the other lakes, and in spring, the water warms more quickly. Oscaleta, middle in size, tends to mix next, and Waccabuc is the slowest to turnover in both spring and fall.

After fall turnover, the lakes will stratify again in the winter as the coldest water comes to the surface, just like ice cubes float on warmer water, and then they will mix again in spring turnover. Although algae blooms often occur at turnover times, because people aren’t apt to be in the water, we rarely post bloom alerts at that time.

The timing of turnover and the chemical composition of the water at turnover can affect the lake water quality in subsequent seasons, so we continue to sample until fall lake turnover is complete, and we also try to collect samples in the spring during turnover. The fully mixed water column provides information on the total amount of nutrients in our lakes.

More information on turnover is on our water and light page.